Belfast had a strong record of women’s political activity during the period 1912 to 1922. The largest Irish women’s organisation of the decade, the Ulster Women’s Unionist Council, was founded in the city in 1911. Nationalist women were also active in Belfast, and prominent among them was Alice Milligan, the editor of Shan Van Vocht. Women in the city also contributed to the British war effort (1914-1918) as nurses and workers in the linen mills that produced cloth for tents and hammocks as well as the linen wrapping for early fighter planes.

See below for more information on locations involved.

The office of the Ulster Women’s Unionist Council was in 33 Ocean Building. The Council was formed in 1911 in response to the planned introduction of home rule to Ireland. It became the largest pre-first world war women’s organisation in Ireland with an estimated 115,000 members. It had an impressive administration with a constitution, affiliation fee and paid secretary.

The popularity of the Council grew rapidly and its membership reflected all classes of Ulster society. The Council undertook a propaganda campaign against home rule through mass rallies and publishing pamphlets. Some members also joined the militant U.V.F. After the outbreak of war, the Council joined the war effort by collecting food and clothes, visiting soldiers’ families and providing comfort and financial help.

Following the establishment of Northern Ireland in 1920, the Council became involved in other forms of political campaigning including the registration of new female voters. The Council celebrated its centenary year in 2011.

Ulster Hall has a long tradition of hosting gatherings of women in Belfast. It was used for meetings and rallies by both the suffragettes and unionist women in the early twentieth century.

Women were not allowed to sign the Ulster Covenant. However, on ‘Ulster Day’ they gathered at the Hall to sign a similar declaration organised by the Ulster Women’s Unionist Council. On ‘Ulster Day’, Ulster Hall became a symbol for unionist women that they too could be patriotic defenders of Ulster and the Union.

Suffragettes also frequently met in the Hall, claiming to have filled it three times over in 1912. Unusually for a venue so symbolic with unionism, it was in Ulster Hall on 13 March 1914 that the suffragettes declared war on Ulster Unionists and publicly criticised Edward Carson for reneging on his promise to expand the franchise to women.

71 Botanic Avenue was the home of Isabella Tod. Tod was a writer and was involved in a number of campaigns in Belfast, including female education, the suffrage, temperance and home rule. She campaigned for women’s education and was secretary of the Belfast Ladies Institute, which used professors from Queen’s University to educate upper-class women.

Tod established the first suffrage society in Ireland in 1871, which proved to be moderately successful: women in Belfast obtained the right to vote in municipal elections in 1887, eleven years before women in the rest of Ireland did so. Tod was also strongly opposed to Home Rule and set up the Women’s Liberal Unionist Association. She travelled around England speaking against Home Rule at public meetings. Furthermore, she organised an anti-Home Rule petition that attracted 20,000 signatures; it was presented to the House of Commons in 1893.

Number 4 College Gardens was the home of doctor and suffragette Elizabeth Bell. Bell was the first woman to qualify as a doctor in Ulster in 1893. She had a practice in Belfast, treating mainly women and young children. She was an honorary physician to the maternity and baby home for homeless and unmarried mothers at Malone Place hospital. During the first world war, she travelled to Malta and worked as a doctor for the British army in the temporary hospitals for injured allied soldiers.

Bell was active in the suffrage movement and a member of both the Irish Women’s Suffrage Society and the Women’s Social and Political Union. In 1911 she travelled to London and was arrested for throwing stones at department stores as part of demonstration activities. She also worked as a doctor for suffragettes who were imprisoned for their activities in Crumlin Road prison in Belfast.

Note: 4 College Gardens no longer exists – it was situated where Deanes at Queen's is now. The image shows numbers 8 and 9 by way of example of the type of house on the street

Queen’s University Belfast was established in 1845. Women were admitted in 1882 to take arts degrees and could enrol in all courses by 1890. In 1908, the university became an independent institution and its charter guaranteed that it would be non-denominational and give equal status to women. A number of well-known Belfast women were elected to the university’s governing body, including the educationalist Margaret Byers, philanthropist Margaret Montgomery Carlisle and Celtic studies academic Mary Hatton.

Queen’s became a site for female political activism in the early twentieth century. Suffragettes held meetings on campus, which occasionally became rowdy events. The women students’ Voluntary Aid Detachment organised war effort activities. However, that group came into conflict with the university in 1915 when women students opposed compulsory ambulance training for female students. A standoff ensued until January 1916, when the measure was suspended by university authorities.

Queen’s elected representatives to the Parliament of Northern Ireland included Eileen Hickey, Irene Calvert and Sheelagh Murnaghan.

Julia McMordie was a philanthropist and political activist. She was a vice-president of the Ulster Women’s Unionist Council and involved in a number of health charities. Health and education issues were the focus of her philanthropic and political career.

McMordie became the first female Belfast city councillor in 1918 and was elected as an alderman in 1920. At sixty-one years and widowed, she was one of only two women elected to the first parliament of Northern Ireland for South Belfast, where she served one term. Although criticised for her infrequent parliamentary contributions, McMordie’s speeches reflected her experience in Belfast city politics and addressed a range of issues, including female police officers, the education of disabled children and the cleanliness of Belfast’s streets.

McMordie Hall in Queen’s University is named after her in recognition of her endowment of the university’s Students’ Union.

Alice Milligan came from a protestant, unionist family and lived on Royal Terrace on the Lisburn Road while attending the Methodist College. Despite this, she became a supporter of Irish nationalism and joined the Gaelic League and the Irish Women’s Association. She initially became involved in nationalism through writing and was co-editor of the Northern Patriot and the nationalist, monthly magazine Shan Van Vocht. She was later appointed as a full-time travelling lecturer for the Gaelic League.

Milligan participated in the centenary celebrations of the 1798 rebellion. She held a number of organisational positions, including secretary of the Belfast centenary committee. She was in London at the time of the Easter Rising and attended Roger Casement’s trial while also collecting funds for the families of political prisoners. She later joined the anti-partition league. Although often forgotten, Milligan was a prominent female figure in the Irish cultural and nationalist revival.

The influential educationalist Margaret Byers founded the Ladies Collegiate School in Belfast in 1859. The school was later re-named Victoria College in 1887. Byers supported reforms in the way in which girls were educated. The school grew rapidly due to the increased interest in educating girls in the late nineteenth century. The school encouraged academic excellence but also taught the skills required for homemaking. After petitioning by Byers, Queen’s University set exams for the school from 1869. Byers also encouraged students to attend university and carry out philanthropic work such as a mentor scheme with the Victoria Homes for orphans and needy children.

Victoria College was the leading girls’ school in the country and remained open during the first world war. Students participated in the war effort by donating prizes, staging patriotic concerts and knitting socks for soldiers. Victoria College remains a school for girls today but it moved to Cranmore Park in the 1970s.

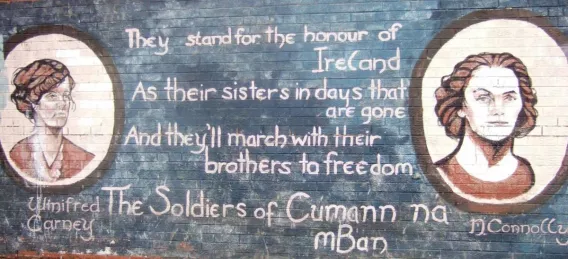

Winifred Carney was a prominent republican, trade-unionist and feminist in early twentieth-century Belfast. She was member of the militant Citizen Army and Cumann na mBan, and became president of the Belfast branch of Cumann na mBan in 1917. Through her involvement in the trade union movement, Carney became friendly with James Connolly. She served as his personal secretary and was fully informed of the 1916 Rising plans. She was stationed with Connolly at the G.P.O. during the Rising itself, typing dispatches and performing nursing duties.

Carney was interned in Aylesbury prison for her role in the Rising. She unsuccessfully stood as a candidate in the 1918 Westminster election as one of only two female Sinn Féin candidates. She blamed her poor result on a lack of support from the party. Carney later opposed the treaty and was known to harbour republicans such as Markievicz and Austin Stack at her home in Carlisle Circus.

The Cumann na mBan mural celebrates Belfast women’s involvement in the Irish independence movement. The organisation was founded in Dublin in 1914 to support the work of the Irish Volunteers. The Belfast branch was established in 1915 and attracted prominent female nationalists, including James Connolly’s daughters, Nora and Ina.

The Belfast branch was considered to be exceptional as it trained members in first aid, military drills and rifle shooting similar to the Irish Volunteers. It was active during the Easter Rising, with three contingents travelling to Dublin and stationed at Liberty Hall. These women were responsible for finding the leaders of the Rising on Easter Sunday morning to tell them Eoin MacNeill had called off the Rising.

Later, Cumann na mBan campaigned for Countess Markievicz and Winifred Carney in the 1918 election. After partition, however, Cumann na mBan’s membership in Belfast declined because many of its prominent members had left the city as a result of political harassment.

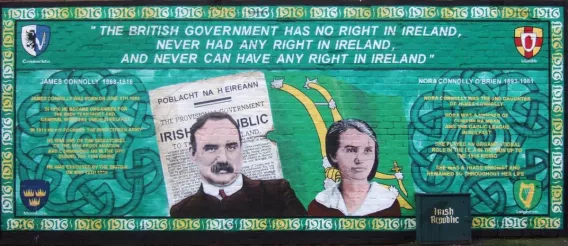

Glenalina Terrace on the Falls Road was home to the Connolly family after they settled in Belfast in 1911. Nora Connolly and her sister Ina became involved in labour and republican movements – they set up the Belfast branch of Cumann na mBan and joined Na Fianna Éireann.

Nora became a prominent republican activist. She smuggled arms, carried messages to the U.S. for the I.R.B. leadership and brought the deported Liam Mellows back to Ireland prior to the Easter Rising. During the Rising, she and Ina were sent back to Tyrone with a message from Patrick Pearse to assemble the Northern Division of the Irish Volunteers. After the Rising and their father James’s execution, the family left the Falls Road. Nora travelled to the U.S. and undertook a speaking tour about Irish nationalism. She remained active in the labour movement throughout her life, although she had a fractious relationship with the Irish Labour party.

Nora Connolly is commemorated on a number of murals around Belfast. The one pictured here is on Clondara Terrace on the Falls Road and is dedicated to Nora and her father.

Dame Dehra Parker was the most successful female M.P. in the parliament of Northern Ireland (which met in Stormont Castle). She was one of two women first elected in 1921 and she retained her seat until 1960. She was the only woman to hold a senior ministerial office in the parliament, serving as parliamentary secretary for education in 1937 and minister for health and local government in 1949. Her outstanding achievement was the introduction of the national health service to Northern Ireland.

Parker was a staunch unionist and opposed any measure that she thought would strengthen nationalists. She led the campaign to abolish proportional representation, defended legislation that encroached upon civil liberties and supported the introduction of promissory oaths for those employed by the government. When she retired in 1960, she was succeeded by her grandson and future prime minister of Northern Ireland, James Chichester-Clark.