A researcher at University of Limerick has played a key role in examining some of the secrets behind Game of Thrones.

What are the secrets behind one of the most successful fantasy series of all time? How has a story as complex as the one in George R.R. Martin’s novels enthralled the world and how does it compare to other narratives?

Researchers from five universities across the UK and Ireland – including UL’s Dr Pádraig MacCarron - came together to unravel ‘A Song of Ice and Fire’, the books on which the TV series is based.

In a paper that has just been published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, the team of physicists, mathematicians and psychologists from Coventry, Warwick, Limerick, Cambridge and Oxford universities used data science and network theory to analyse the acclaimed book series by George R.R. Martin.

The study shows the way the interactions between the characters are arranged is similar to how humans maintain relationships and interact in the real world. Moreover, although important characters are famously killed off at random as the story is told, the underlying chronology is not at all so unpredictable, the research shows.

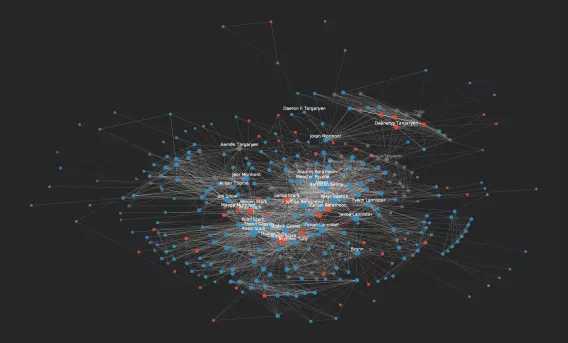

The team found that, despite over 2,000 named characters in ‘A Song of Ice and Fire’ and over 41,000 interactions between them, at chapter-by-chapter level these numbers average out to match what we can handle in real life.

Even the most predominant characters – those who tell the story - average out to have only 150 others to keep track of. This is the same number that the average human brain has evolved to deal with.

While matching mathematical motifs might have been expected to lead to a rather narrow script, George R. R. Martin keeps the tale bubbling by making deaths appear random as the story unfolds. But, as the team show, when the chronological sequence is reconstructed the deaths are not random at all: rather, they reflect how common events are spread out for non-violent human activities in the real world.

“These books are known for unexpected twists, often in terms of the death of a major character, it is interesting to see how the author arranges the chapters in an order that makes this appear even more random than it would be if told chronologically,” explained Dr Pádraig MacCarron, a postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for Social Issues Research and Mathematics Applications Consortium for Science and Industry (MACSI) at UL.

“Social networks of the most connected characters, while seemingly extensive, mirrored the typical range of social networks that humans maintain. Furthermore, characters’ social networks did not extend beyond the cognitive limit of social connections that humans are able to sustain.

“Although the time intervals between significant deaths in relation to the story’s timeline may appear random, they are not told in chronological order. Re-arranging them in order of which they occur, they follow a pattern more commonly observed in reality,” added Dr MacCarron.

‘Game of Thrones’ has invited all sorts of comparison to history and myth and the marriage of science and humanities in this paper opens new avenues to comparative literary studies. It shows, for example, that it is more akin to the Icelandic sagas than to mythological stories such as the Táin Bó Cúailnge or Beowulf. The trick in Game of Thrones, it seems, is to mix realism and unpredictability in a cognitively engaging manner.

“People largely make sense of the world through narratives, but we have no scientific understanding of what makes complex narratives relatable and comprehensible. The ideas underpinning this paper are steps towards answering this question,” explained Professor Colm Connaughton, from the University of Warwick.

Fellow researcher Professor Robin Dunbar, from the University of Oxford, observed: “This study offers convincing evidence that good writers work very carefully within the psychological limits of the reader.”