COVID does not destroy so much as reveal weakness. Associate Professor of Economics at University of Limerick, Stephen Kinsella writes on how “it is in our power to buttress the weaker parts of our society and economy revealed by the COVID crisis”.

We know those most likely to suffer directly for the health effects of the crisis are older, sicker households. We know those most likely to suffer indirectly are younger, poorer households. We know sectors like accommodation, retail, events, and tourism are having the worst year on record. We know Ireland's arts and entertainment sectors have been hit harder by COVID than in any other EU country.

We know sectors like pharmaceuticals and ICT are having their best year on record. Ireland’s SMEs are struggling to survive, while Ireland’s multinationals are thriving. COVID is a distributional variable.

If the virus shows where we are weak, it also reveals where we are strong. Studying the economic impact of the crisis, and contributing to the research expert advisory group of the National Public Health Emergency Team has taught me a lot about where we might strengthen our society over the next few years. Here are my thoughts on how to do that.

Community responses typically trump national responses

The national response to the virus gets all the headlines, and that is natural for a highly centralised economy like ours with a population of less than 5 million people. Far from the headlines however, it is the community response that has simultaneously helped secure buy-in for restrictive measures and reduced the negative impacts of those measures.

For example, when vulnerable households were asked to cocoon, the community response around helping buy food, walk pets, see to loved ones, and more was very strong in Ireland relative to other countries.

The Limerick COVID-19 Community Response led the way nationally, particularly through its helpline service. Measures to increase, deepen, and amplify the work communities have done so far will be crucial in maintaining social solidarity as we learn to live long term with the virus.

Research is everything

Research is gathering information needed to answer a question. There is no bigger question in the world than ‘how to beat COVID’. UL has led the way nationally in the research effort to understand COVID. Several faculty members add their expertise to NPHET, more are working on research projects funded by Science Foundation Ireland and the Health Research Board. We know far more than we did in February of 2020, but we still have so much more to learn. The more we learn, the more we can help. The Resilience and Recovery plan has a strong focus on using a research-led approach to the crisis. The Government writes:

"We shall seek to build on this initial work to deliver a nationally coordinated research effort, with the necessary research infrastructure and funding, to manage and respond to the health, social and economic consequences of the pandemic and enhance our preparedness and resilience for future emergencies."

COVID and the research response to it are a university-wide priority. UL and UL’s Research office led by Professor Norelee Kennedy are working on new initiatives so that research teams can make the largest contribution possible to the

COVID relief effort.

There is no tradeoff between the health of the people and the health of the economy

Economists at the start of the crisis assumed there would be a tradeoff between the health of the economy and the health of society. Lockdown the economy and you save lives, but gross domestic product, a measure of economic progress, would surely fall. Let the virus run wild without lockdowns, and you would have many deaths, but with a far smaller impact on economic growth.

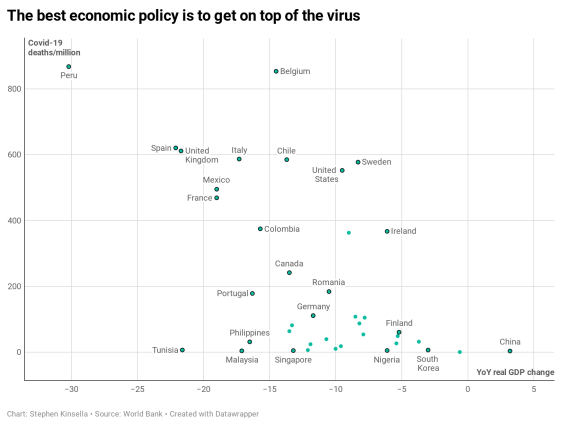

The economists got it wrong. There is no tradeoff between the health of people and the health of the economy. The chart shows deaths from COVID per million on the vertical axis, measured against the change in gross domestic product from the second quarter of 2019 to the second quarter of 2020, the latest data available. If the economists were right, a country like Peru, with over 800 deaths/million, would have a very low fall in economic growth. Instead it has had the highest. A country like Finland, or South Korea, which had a very hard lock down, would have had very large falls in growth. It is the opposite.

Countries that have protected their people have protected their economies.

You can see the reading for Ireland--we are solidly mid-tier here, recording 367 deaths/million and a fall of -6.2% in inflation-adjusted gross domestic product. That doesn’t mean lockdowns are great ideas. The macroeconomy might not suffer, but the microeconomy is where people actually live and work.

There is a strong role for policy in offsetting the worst effects of the crisis for the hardest hit sectors, in terms of replacing lost incomes, lost turnover, lost opportunities.

The other role is in retraining workers whose jobs will not, despite the best efforts of government, come back. Some firms will fail, some sectors will be forced by the crisis to transform how they do what they do, and this may include education.

Thinking carefully about what the shape of that retraining effort might be, who might deliver it, and what kind of Ireland might result from all of this change is the task COVID has set us. The good news here is that we are strong in this area already. UL is where the future happens anyway. We have the students, we have the staff, we have the facilities, we have the ideas. We can build a post-COVID future here first if we are given the opportunity to do so.

- Professor Stephen Kinsella